A Johns Hopkins University-led research team has developed a pill-sized capsule that, when swallowed by a patient, can diagnose, monitor, and treat gastrointestinal diseases including Barrett's esophagus, a condition known to be a precursor to esophageal cancer. Called the multifunctional ablative gastrointestinal imaging capsule (MAGIC), it's a faster and cheaper method that could replace traditional tube-based endoscopies, which are expensive and invasive.

"The advantage of an easy-to-swallow tethered capsule is that there is no need for sedation and no recovery time, so we can screen more patients and detect earlier stages of disease in an office setting, in less than 10 minutes," said senior author Xingde Li, a professor of biomedical engineering at JHU. "With our device, doctors can not only detect gastrointestinal problems but also treat them, all within a single procedure."

The team's findings are published in Science partner journal Biomedical Engineering Frontiers (BMEF).

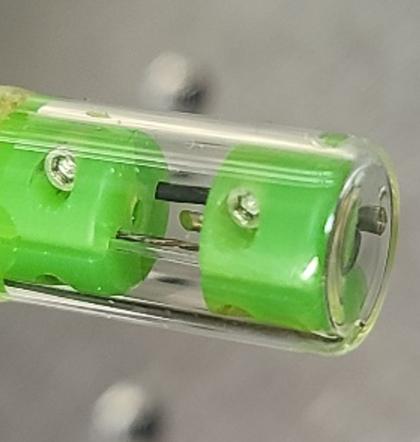

During a capsule endoscopy test, the patient swallows a pill—about the size of two multivitamin pills—attached to a string. As the capsule moves through the esophagus, tiny cameras inside the pill take pictures of fine structures not only on, but also below, the esophagus surface. These images are sent to a recording device for the doctor to interpret.

While capsule endoscopes have been around for many years, drawbacks to their more widespread use when compared to conventional endoscopies remain. One example is that the capsules capture images at only one wavelength, limiting their ability to produce clear images of esophageal lesions.

In contrast, the MAGIC operates with dual wavelengths and can achieve an imaging resolution far surpassing existing tethered capsule technology, says the study's lead author, Hyeon-cheol Park, a research associate in the Department of Biomedical Engineering. The ultra-small but powerful cameras can detect even subtle changes in the lining of the esophagus, making it possible for doctors to spot early lesions with remarkable precision.

Another challenge of existing tethered capsule technology is the capsules move through the body without visual guidance, so doctors can't see where those devices are going. To address this, the Hopkins researchers equipped their capsule with a tiny traditional endoscopy camera, so images are readable in real time on a monitor.

"Our capsule provides all the benefits and capabilities of sedated endoscopy but in much less time," said Park. The team is also upgrading the capsule to perform laser ablation. This means that if a doctor spots a potentially dangerous lesion, they can remove it on the spot. This functionality has never been demonstrated before, Li said.

"We envision this as a true 'one-stop-shop' device for doctors to diagnose and treat a patient in a single visit, with a single procedure. This could really change the game for the early screening of esophageal cancer and is a project that we are very excited about," said Li.

Having determined that the technology works successfully with in vivo studies, Li's team is planning a pilot patient study within the next year to determine its real-world effectiveness.

Other members of the study team include Dawei Li from the Johns Hopkins Department of Biomedical Engineering; Rongguang Liang, a professor of optical sciences at University of Arizona; and Gina Adrales, associate professor of surgery at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.